Virtual Discussion: Indigenous Position in the Forestry Sector Development

In Collaboration with Forest and Society Research Group and IFSA LC ULM

Can we protect the indigenous people while protecting our forest simultaneously? As an individual, it is very daydreaming to say yes on the spot spontaneously. While this question will take so many times for many stakeholders to decide if we can do it or not? It shows if the dream of a future resilient forest needs to be managed through its social problem. Then, where is the indigenous people’s position in the forestry sector development? And to what degree should we give them a position? IFSA LC UNHAS, FSRG, and IFSA LC ULM brought up this crucial issue through a virtual discussion on 30 November 2022.

- From Marginalized to Indigenous

Emban Ibnurusyd Mas’ud, Forestry Faculty of Universitas Hasanuddin, presenting the view of academics on indigenous people in the forest.

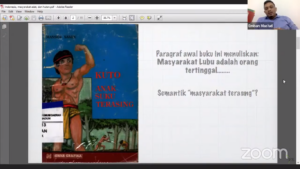

Kuto Anak Suku Terasing (ind) or Kuto, the child of the marginalized tribe (eng), was a children’s old book that told the lifestyles differences between some children in elementary school. Kuto’s friends have parents with city-based jobs, while Kuto’s family lives in a shifting cultivation culture. This book describes the Kuto lifestyle as non-modernizes life and is marginalized. Semantically, it has given such a perception that indigenous people live in a condition with no electricity, no formal education, not enough hygiene place, or even have no understanding or willingness to change and adjust to the modern world.

This perception has led to misconceptions about defining the indigenous itself. Underestimating perception by thinking that the “marginalized” people do not have enough capacity to manage forest sustainability is one of the biggest threats.

As Indonesia has acknowledged the importance of mega-diverse culture, while at the same time, the issue of land claiming is becoming a significant issue in Indonesia’s Forestry Sector. The Forestry and Environmental Government of Indonesia then set verified variables to analyze indigenous people’s genuineness to be recognized and given rights to manage the forest. Those verified variables are their history, community, governmental structure, places with clear boundaries, bureaucracy, and wealth/customary subjects. Those variables were set to ensure the indigenous people can protect the sustainable forest. Mr. Emban as a researcher, also stated that when we are talking about indigenous people, we can’t only imagine marginalized people with low or even no sense of modernity. But people fully understand what they do and their position in society.

- A Story From Indigenous Person

Martha Doq, Indigenous Person from Dayak Bahau Tribe, presenting the forest management in her tribe, Kalimantan, Indonesia.

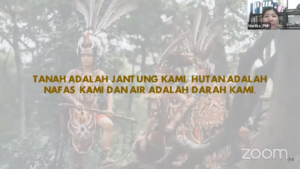

While Mr. Emban gave insight from the academic side, Mrs. Martha Doq presented her works together with her friends from the same tribe. She also presented the woman’s community that supports the recognition from the government for the Dayak Bahau Umaq Suling Long Isun tribe to be able to manage their forest. As a warrior, her steps are yet to finish. Dayak Bahau has a powerful proverb describing their love for the earth: “Land is our heart, the forest is our breath, and water is our blood.” Regarding climate change and industry that changes the forest landscape, the Dayak Bahau Umaq Suling Long Isun, from the side of women, also has a special proverb: “Woman can only give birth to a baby but not a land.” This proverb tells us that the human population is increasing while the forest is decreasing over the years. Moreover, this proverb also incentivizes the Dayak Bahau Umaq Suling Long Isun indigenous people to protect their forests. One of their ways is to ask the government for recognition and access to manage the forest.

Mrs. Martha also explained the forest management on Dayak Bahau Umaq Suling Long Isun, where all the lands have been divided according to utilization. They can be found in the table below.

| Land Name | Utilization |

| Tanaaq Umaaq | Village area. |

| Tanaaq Lepu’un Lumaq | The land of the former cultivation area is planted with fruits. |

| Tanaaq Lepu’un Umaaq | The land of the former village containing several fruit plants and/or other crops. |

| Tanaaq Dioq | Land areas that are managed by the community but there is a disaster and are abandoned. People can only work on the land if certain traditional ceremonies have been held. |

| Tanaaq Kasoq | Land reserved for indigenous peoples as a hunting ground. |

| Tanaaq Tanam | Burial area, the coffin is buried in the land. |

| Tanaaq Salung | Burial area, the coffin is not buried in the land/left in the cave. |

| Tanaaq Berahan | Land used as a place to do business, especially in terms of collecting forest products for a living. |

| Tanaq Lung | Land, that the community cannot manage, is guarded for the future. |

| Tanaaq Peraaq | Land that functions as a reserve forest area. |

| Tanaaq Pukung Buaaq | Area to take medicinal herbs, fruits, and so on. |

| Tanaa Jakah | The former area saw bloodshed, war events, and unnatural deaths. This area can be processed by the community when traditional rituals have been carried out (Adat Tutung Urip). |

| Tanaa Nah | An area that never runs out of water despite the dry season. This place is usually visited by animals to drink because of its salty taste. In the indigenous Dayak Bahau Umaaq Suling, there is also a category |

- The Youth Voice (IFSA LC ULM)

From the side of the youth, Hilman Fahmi from IFSA LC ULM shared his story on how people in his place appreciate the forest through many ways like a ritual ceremony which has deep philosophy regarding how forest have benefited them in life.

In closing, the discussion concludes if indigenous people are not marginalized people of modernity. Indigenous people have the same position level as everyone who can think and decide what is better for their future. This is why it is important to always incorporate them into the planning, especially in the forestry sector development, as they also have ecological knowledge, which will be so helpful for shaping the future resilient forest together.

Author: Wening Ila Idzatilangi